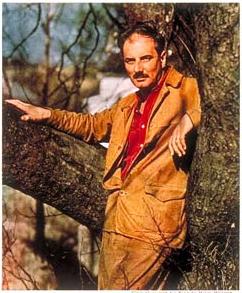

Lewis Mumford, American social philosopher, and one of the leading thinkers and writers of the 20th century.

Born in Flushing, New York, Mumford assiduously and single-mindedly devoted himself to writing. Over a period of 60 years, Mumford wrote some thirty books, covering subjects as diverse as the history of cities, the history of machine technology, art and architectural criticism, and literary criticism. He is most widely known for the books The City in History and The Myth of the Machine: The Pentagon of Power. He passed away on 26 January 1990. Though widely honoured during his lifetime, with fellowships, professorships, awards and honorary doctorates, he remains largely unknown in his native America.

Mumford may be seen as one of those who have enabled today’s environmental consciousness. Environmental historian Ramachandra Guha has referred to him as ‘the patron saint of environmentalism’. Mumford's ‘organicist’ philosophy was deeply ecological. His varied concerns converge on the problem of defining an ethic which would fuse the classical socialist values of justice and community with what we would today call environmental values. As early as 1930, we find him writing that the three main threats to modern civilisation were the destruction of forest cover, the depletion of non-renewable resources, and the awesome destructive power of modern weaponry. His first major work, Technics and Civilisation (1934), underlined the links between industrialisation, the increasing intensity of energy use, and pollution.

Born in Flushing, New York, Mumford assiduously and single-mindedly devoted himself to writing. Over a period of 60 years, Mumford wrote some thirty books, covering subjects as diverse as the history of cities, the history of machine technology, art and architectural criticism, and literary criticism. He is most widely known for the books The City in History and The Myth of the Machine: The Pentagon of Power. He passed away on 26 January 1990. Though widely honoured during his lifetime, with fellowships, professorships, awards and honorary doctorates, he remains largely unknown in his native America.

Mumford may be seen as one of those who have enabled today’s environmental consciousness. Environmental historian Ramachandra Guha has referred to him as ‘the patron saint of environmentalism’. Mumford's ‘organicist’ philosophy was deeply ecological. His varied concerns converge on the problem of defining an ethic which would fuse the classical socialist values of justice and community with what we would today call environmental values. As early as 1930, we find him writing that the three main threats to modern civilisation were the destruction of forest cover, the depletion of non-renewable resources, and the awesome destructive power of modern weaponry. His first major work, Technics and Civilisation (1934), underlined the links between industrialisation, the increasing intensity of energy use, and pollution.

Mumford recognised that ecological degradation was, at least in part, the outcome of a flawed value system which had “missed the great lesson that both ecology and medicine teach - that man’s great mission is not to conquer Nature by main force but to co-operate with her intelligently and lovingly for his own purposes.” Ecological degradation, he believed, is inescapable in an economic system driven by the belief that quantitative production had no natural limits. Indeed modern technology is profoundly anti-ecological - “driven by the desire to displace the organic with the synthetic and the pre-fabricated”, it exhibits a “barely concealed hostility to living organisms, vital functions, organic associations.”

Mumford anticipated the alternate theorists of today. He was a critic of both capitalism and communism, holding them to be but two variants of a centralising, destructive and violent system of production. But he did not wholly turn his back on modern technology, seeking instead to bend it to serve human and environmental needs.

In an age of specialisation, Mumford was a sociologist, philosopher, cultural historian, art and literary critic, and authority on architecture and city planning, a true Renaissance man. In 1923, Mumford was a founding member of the Regional Planning Association of America, an experimental group that paved the way for several projects in regional development, including the Tennessee Valley Authority. In 1932 Mumford began to write a column of architectural criticism, ‘The Sky Line’, for the New Yorker.

Mumford was deeply influenced in his youth by the work and thought of Patrick Geddes, the eccentric Scottish biologist, town planner, educator and peace activist (1854-1932). For Mumford, Geddes’ work provided the basic direction and the skeleton which he then added flesh to. In 1938, as consultant to the City and County Park Board in Honolulu, Hawaii, the follower of the ‘garden city’ Master prepared a booklet Whither Honolulu? based on his study of the parks and playgrounds of that city. Again, recalling Geddes’ efforts at organising ‘cities exhibitions’, in 1939, Mumford worked on a documentary film The City which was shown at the city planning exhibit at the New York World’s Fair.

Geddes’ young son Alisdair was killed in the First World War. He saw Alisdair in Mumford and wanted him to assist him in his work. Mumford was very oppressed with Geddes seeing in him the return of his dead son. Later, after his own son, who was named Geddes, was killed in the 2nd World War, by which time Patrick Geddes was no more, Mumford became a leading propogator of Geddes’ thinking and diligently assisted his biographers.

Mumford was deeply interested in India. He studied Indian history and religion and closely followed Geddes’ town planning work in India. Mumford was personally acquainted with Radhakamal Mukherjee, the Indian professor of sociology and disciple of Geddes, whose work dwelt on human interactions with nature - which he called ‘social ecology’. Mukherjee has written extensively on the ecological basis of civilisation in Gangetic Bengal, culminating in the emergence of Calcutta as a metropolis - but one that makes a dysfunctional break from its ecological and social roots.

No comments:

Post a Comment